A building that was mostly demolished on Wednesday, May 30, 2018, once helped to protect enriched uranium at Y-12, and it was used by military police and the Oak Ridge Police Department to help protect the city. Part of the building, a former secure federal communications center, was still standing among the demolition debris late Wednesday afternoon. This picture was taken looking southeast from near the intersection of Bus Terminal Road and Oak Ridge Turnpike. (Photo by John Huotari/Oak Ridge Today)

Note: This story was last updated at 8:30 a.m. June 2.

A building that was mostly demolished on Wednesday once helped to protect enriched uranium at Y-12, and it was used by military police and the Oak Ridge Police Department to help protect the city.

The building at 101 Bus Terminal Road was once connected by radio to a Y-12 building that stored the world’s only supply of enriched uranium-235, according to a 2010 newspaper article published by D. Ray Smith, who cited Bill Sergeant, head of security after World War II.

A small section of the Bus Terminal Road building that still had historic artifacts—two holding cells and a heavy, bulletproof steel door—remained standing, surrounded by demolition debris, on Wednesday and Thursday. It’s not clear why that one section hadn’t been demolished yet, but the 2010 newspaper article by Smith said it had been a secure federal communications center and was built to be safe from attack. That small section of the building, which had no external windows, was reported to have a concrete ceiling that was one foot thick.

The building, which is at the intersection with Oak Ridge Turnpike, is now being completely demolished so a Taco Bell restaurant can be built there. The building had been extensively modified, and it’s not clear how much of it might have been considered historic.

Smith said the Bus Terminal Road building was once connected by radio to Building 9213, which stored uranium-235 for about a year at Y-12. Building 9213 is on the south side of Chestnut Ridge, which is on the south side of Y-12. After it briefly stored uranium, Building 9213 was used for criticality experiments for years, Smith said. It’s also been used to train the National Guard to identify and isolate radioactive sources as part of their training for homeland security.

In the 2010 article, Sergeant said Building 9213, which has walls that are 18 inches thick, was his top security concern in 1946, after World War II had ended. Officials were concerned that hostile forces could launch an attack to try to capture the valuable uranium-235, which was stored in a bank-type vault. Federal officials wanted security forces, including those at the Bus Terminal Road building, to know immediately about any such attack, Smith said.

Depending upon its enrichment level, uranium-235 can be used in nuclear reactors or nuclear weapons. Oak Ridge had uranium-235 because it was built as part of the Manhattan Project, a top-secret project to build the world’s first atomic weapons during World War II.

In the 1940s, the Bus Terminal Road building had signs on it that referred to it as the headquarters of the Auxiliary Military Police, headquarters of the Guard Department, and headquarters of the Security Forces, according to pictures taken by government photographer Ed Westcott. The photos, including one that has not been published before, were shared by Don and Emily Hunnicutt, Westcott’s daughter and son-in-law.

Part of the Bus Terminal Road building that was shown in those photos from seven decades ago was demolished long ago, and much of the rest of the building was reported to have had extensive interior modifications.

It’s not clear when the Oak Ridge Police Department moved into the building. The Police Department was earlier at the town hall at Kentucky and East Tennessee avenues in Jackson Square, according to documents provided by Don Hunnicutt.

Police headquarters appear to have been located in the Bus Terminal Road building on Oak Ridge Turnpike by late 1946 or later, according to the documents. (There were also guard headquarters at that time at Robertsville and Raleigh roads, and military police headquarters and barracks in the West Village dormitory area.)

Smith said the use of calutrons to enrich uranium at Y-12 stopped in December 1946, and at some point, most of the uranium storage went back to the K-25 site, where gaseous diffusion was used to enrich uranium. It’s not clear if the change in uranium-235 storage eliminated the need for a radio connection between Building 9213 at Y-12 and the Bus Terminal Road building in central Oak Ridge.

Some residents, including Hunnicutt, remember going to the Police Department when it was on Bus Terminal Road to get their driver’s licenses. Hunnicutt said he took the driver’s license test in 1960, driving around the block using a series of left-hand turns. He had to make sure to use his left-turn signal when making the turns, and that was essentially it.

City court was also once located in the building, and it was later used by Oak Ridge Utility District, a natural gas supplier. The building was last used by Anderson County General Sessions Court, Division II, in Oak Ridge. The courthouse had been there since 2009, but it moved this year to renovated space in a county-owned building on Emory Valley Road.

There are now a half-dozen or fewer well-known historic buildings on the city’s two main roadways, Oak Ridge Turnpike and Illinois Avenue. They include the Red Cross building and Tunnell Building near the Bus Terminal Road building, Wildcat Den/Midtown Community Center a few miles west, and Brannon House several miles east, next to the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Scientific and Technical Information; and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) building on South Illinois Avenue. There are others that are not on the city’s two main thoroughfares.

There was no organized public opposition to demolishing the Bus Terminal Road building. Those who advocate for at least some historic preservation suggest they have to prioritize.

“Oak Ridge Heritage and Preservation Association feels that any time a World War II-era building is torn down, it is a loss,” ORHPA President Michael Stallo said. “However, we need to be thoughtful in choosing which buildings to try to save. It can be an uphill battle to stop the demolition of historic structures. Although it would be another one lost, there are a couple that would have a higher priority. The stone house (Brannon House) on the Turnpike is one of our biggest concerns at the moment. It is a unique structure in that it was built just before Oak Ridge was picked as the headquarters for the Manhattan Project. Also the former Stone and Webster Field Hospital on Illinois Avenue—now the NOAA building—is one of the more important ones. It was one of the earliest buildings built. It was a field hospital for the workers that were constructing the Y-12 buildings.”

A building that was mostly demolished on Wednesday, May 30, 2018, once helped to protect enriched uranium at Y-12, and it was used by military police and the Oak Ridge Police Department to help protect the city. Part of the building, a former secure federal communications center, pictured above, was still standing among the demolition debris late Wednesday afternoon. It included a heavy, bulletproof steel door and two holding cells. (Photo by John Huotari/Oak Ridge Today)

Historic preservationists have expressed a desire to work with city officials in at least some cases, possibly with historic zoning.

“We can’t save every building, but with each loss, it makes those that remain all the more important,” said Mick Wiest, ORHPA executive director.

Some in the historic preservation community wish the city could do more to preserve at least some historic structures.

Asked about this week’s demolition and whether the city can be or should be involved in helping to preserve historic properties, such as with historic zonings, Oak Ridge Mayor Warren Gooch said there are more than 5,000 legacy buildings in the city, not six. Gooch is presumably referring to the many World War II-era homes that remain in the center of the city, Manhattan Project buildings at the federal sites, and other wartime structures such as the Grove Center and Jackson Square shopping centers.

“As mayor, I am focused on the future: Blankenship Field, the new American Museum of Science and Energy, the new Pre-K (preschool), new roofs on schools, new Senior Center, the next phases of Main Street, a new water plant to replace a 75-year-old one, repaving streets while dealing with the loss of state taxes (Hall Income Tax)—$700,000 when fully repealed—(and) a shortfall in Roane County sales tax, currently $750,000 through March due to Oak Ridge National Laboratory exemptions,” Gooch said. “However, you can ask Rick Dover, developer of the Alexander Inn, about my support for saving real historic properties (not jail cells). In the meantime, I have to deal with real challenges, not hypotheticals.”

A large number of wartime structures have already been demolished, including in cleanup work at the federal sites such as the former K-25 site, which has been shut down since the mid-1980s, and wartime dormitories, barracks, homes, and other facilities. Built when the United States was racing to build an atomic bomb before Germany could, many of those buildings were not intended to be permanent. Many of the demolished structures have been “behind the fence” or in secure areas at the federal sites. One goal at the federal sites, and in the city itself, has been to modernize.

The Alexander Inn project that was cited by Gooch was one of the buildings that historic preservationists had lobbied most heavily to save. It has since been preserved and converted into an assisted living center. The North Tower at the former K-25 Building in west Oak Ridge was another. Although it couldn’t be saved, an agreement signed more than five years ago calls for a viewing tower, history center, and replica equipment building at the south end of the former mile-long, U-shaped K-25 Building, which was once the world’s largest building under one roof.

Echoing Gooch, at least to some extent, Oak Ridge City Manager Mark Watson said there are many needs and projects in town.

“Historical preservation efforts are limited to the interests of the individual owner or an adopted effort of the community, unless there is a partnership and active public interest in preserving a particular building by more than just the city government,” Watson said.

“As Warren pointed out, the Alexander was a great adaptive reuse,” Watson said. “But it cost lots of money! The public money (a $500,000 grant) helped entice the developer to come.”

The Alexander Inn building, once known as the Guest House, had been dilapidated before it was renovated, and the project would reportedly not have worked without the grant.

Watson said Oak Ridge has a National Historical District established for the entire legacy areas of the city.

“Owners can get historical tax credits if they choose,” he said. But, “very few have taken advantage of this despite the tax incentive.”

Some buildings may not be preserved. Watson said the city will get the New York Avenue (Pine Valley) school back. That building now houses the Oak Ridge Schools Preschool and School Administration Building. But the necessary repairs to that building are expected to cost more than the building is worth, and a new preschool is being built at Scarboro Park.

“There will not be an effort to retain this city property because we will need to consider using the land for future housing initiatives,” Watson said.

Pictured above is the interior of what has been described as a former federal secure communications center. It had a heavy steel door described as bulletproof and two holding cells. The building at 101 Bus Terminal Road had been used by both military police and the Oak Ridge Police Department. (Photo by John Huotari/Oak Ridge Today)

A few of the World War II-era buildings at the three large federal sites, including the K-25 Building, are expected to be part of the two-year-old Manhattan Project National Historical Park. That new park is helping to tell the story of the top-secret Manhattan Project at three of its wartime sites: Oak Ridge; Hanford, Washington; and Los Alamos, New Mexico.

There is some difference of opinion over how much attention to pay to the city’s history. At a community forum a few years ago, some high school students said the city spends too much time talking about its past. But those who have sought to preserve parts of the city’s history have cited the military and scientific significance of the Manhattan Project, one of the most important developments of the 20th century, and they have recalled Oak Ridge’s unique history since the war, including in areas like nuclear medicine.

Still, one of the primary concerns in the city for more than a decade or so has been the need for more new commercial projects, particularly retail and housing developments that might attract new residents, bring in new sales tax and property tax revenues, and help retain current residents and keep them from shopping in places like Knox County. It’s not clear how the desire for commercial development might be balanced against the desire for some historic preservation in any future projects or if that is possible, especially on the city’s two busy main roadways.

A representative of Tacala Companies, a Taco Bell franchise operator based in Vestavia Hills, Alabama, was not available for comment on Thursday afternoon. Neither was Tony Capiello of Vintage Development Corporation of Knoxville, which had owned the Bus Terminal Road property. Two other nearby buildings, the Tunnell Building and Red Cross building, are listed as available through Capiello Real Estate. Both have received historic preservation awards from ORHPA.

Pictured above is the interior of what has been described as a former federal secure communications center. It had a heavy steel door described as bulletproof and two holding cells. The building at 101 Bus Terminal Road had been used by both military police and the Oak Ridge Police Department. (Photo by John Huotari/Oak Ridge Today)

Seven decades ago, the guard force that used the Bus Terminal Road building, among other facilities in Oak Ridge, had about 1,000 men by the end of the summer of 1943, according to the documents provided by Don Hunnicutt. That was about a year after General Leslie Groves picked Oak Ridge for the Manhattan Project on September 19, 1942. Sergeant told Smith in 2010 that he had about 1,000 military and armed civilians conducting all enforcement, except inside the three main plants (K-25, X-10 (now Oak Ridge National Laboratory), and Y-12).

The documents list a few reorganizations of the guard force in the city, which was then known as Clinton Engineer Works, or CEW. By late 1946 or later, there was an Oak Ridge Police Department on Oak Ridge Turnpike (presumably on Bus Terminal Road) to perform general police functions, Oak Ridge Guard Department at Robertsville and Raleigh roads to protect vital CEW installations not controlled by plant guards or police, and Military Police, who had headquarters and barracks in the West Village dormitory area and were available for emergencies and to protect the perimeter of the federal reservation.

Sergeant, once a member of the Army’s Manhattan District, helped guard the perimeter of Oak Ridge by manning the gates; patrolling the borders with cars, horses, and boats; and providing police work everywhere, including in homes, banks, trailers, dormitories, traffic control, and through arrests for such crimes as murder, drunkenness, and speeding.

Regarding Building 9213 at Y-12, Smith said it was not the only facility that stored uranium-235 in the early days of Oak Ridge, before the storage moved to K-25. Another storehouse, Building 9214, which was first known as Operation Dog and much later became famous as “Katy’s Kitchen,” also stored highly enriched uranium-235 south of Chestnut Ridge near ORNL, Smith said. A hole was dug, he said, and a vault was built for the nuclear material. A covering on the building was designed to make it look like a barn, and there was a silo that actually served as a guard tower, helping to disguise the special storage facility.

Today, Y-12 has the Highly Enriched Uranium Materials Facility. It’s the nation’s central repository for highly enriched uranium, which is considered a vital national security asset.

The Oak Ridge Police Department is now in the Municipal Building on South Tulane Avenue.

More information will be added as it becomes available.

Pictured above is the interior of what has been described as a former federal secure communications center. It had a heavy steel door described as bulletproof and two holding cells. The building at 101 Bus Terminal Road had been used by both military police and the Oak Ridge Police Department. (Photo by John Huotari/Oak Ridge Today)

The building at 101 Bus Terminal Road is pictured above on Friday, May 25, 2018, before it was demolished Wednesday, May 30. The building was once home to military police and the Oak Ridge Police Department, and it most recently served as Anderson County General Sessions Court, Division II. This picture was taken looking southeast from near Bus Terminal Road and Oak Ridge Turnpike. (Photo by John Huotari/Oak Ridge Today)

Headquarters for the Guard Department and Security Forces in Oak Ridge are pictured above on Bus Terminal Road in this 1940s photo by Ed Westcott. An electronic copy of the photo was provided by Don and Emily Hunnicutt, Ed’s daughter and son-in-law. The part of the building pictured extending to the right had not been part of the building in years, although it’s not clear when it was demolished.

This photo, which has not been previously published, shows Auxiliary Military Police Headquarters on Bus Terminal Road on April 22, 1944. The photo was taken by Ed Westcott, official government photographer in Oak Ridge during World War II, and shared by Don and Emily Hunnicutt. This part of the building was removed years ago, although it’s not clear when that occurred.

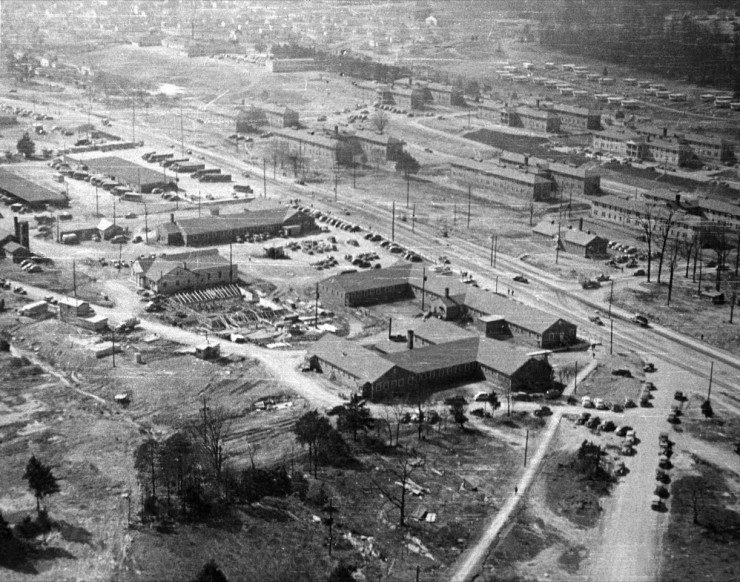

This aerial picture taken by government photographer Ed Westcott in 1943 shows the L-shaped Tunnell Building on Oak Ridge Turnpike at bottom-center, the Bus Terminal Road building up and to the left of it, Security Square past that, and the Red Cross building across from the Tunnell Building. There are dormitories on the other side of Oak Ridge Turnpike, in the area now occupied by the Methodist Medical Center campus. (Photo by Ed Westcott shared by Don and Emily Hunnicutt)

Do you appreciate this story or our work in general? If so, please consider a monthly subscription to Oak Ridge Today. See our Subscribe page here. Thank you for reading Oak Ridge Today.

Copyright 2018 Oak Ridge Today. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed.

Leave a Reply