Note: This story was last updated at 3:30 p.m.

Construction on a mercury treatment plant at the Y-12 National Security Complex could start in 2018 and cost $146 million, a federal official said Wednesday.

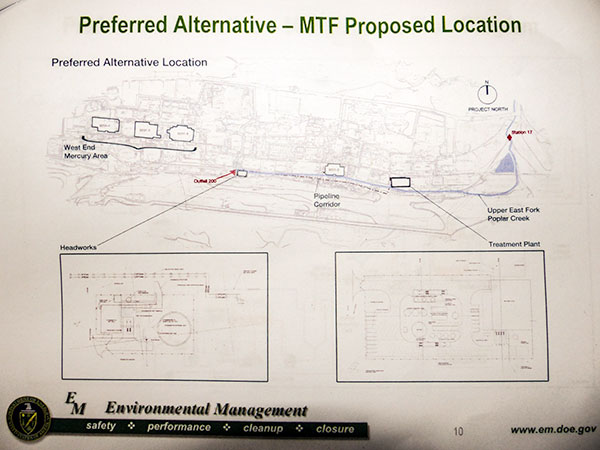

The plant would treat mercury contamination that originates in the West End Mercury Area at Y-12, flows through storm drains, and enters Upper East Fork Poplar Creek at a point known as Outfall 200. East Fork Poplar Creek flows through Oak Ridge.

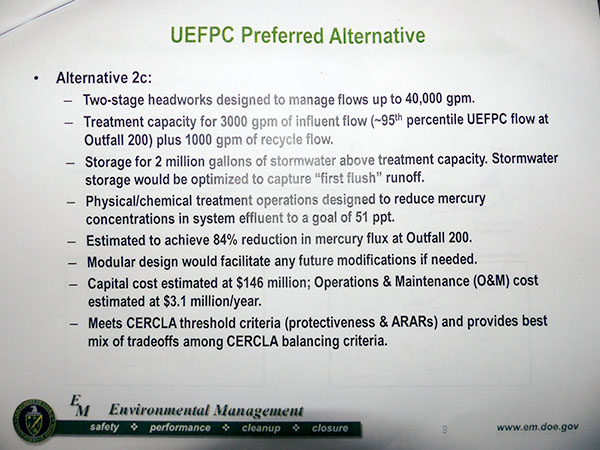

The U.S. Department of Energy has evaluated several alternatives for treating the mercury, including doing nothing. But DOE prefers an option that would treat 3,000 gallons of contaminated water per minute and store two million gallons of stormwater. It could reduce the flow of mercury, a toxic metal, by an estimated 84 percent.

Mercury is no longer used at Y-12, but it was used there in the 1950s and 1960s to separate a lithium isotope for nuclear weapons, said Jason Darby, deputy federal project director for the proposed Mercury Treatment Facility, or MTF. He said all the mercury at Y-12 now is legacy waste.

The new mercury treatment plant was announced in May 2013 in a press conference featuring U.S. Senator Lamar Alexander and Mark Whitney, a former environmental management manager in the DOE Oak Ridge Office who now works at Energy Department headquarters in Washington, D.C.

“This water treatment plant is a major step in addressing one of the biggest problems we have from the Cold War era—mercury once used to make nuclear weapons getting into our waterways,” Alexander, a Tennessee Republican, said at the time.

On Wednesday, Darby said mercury cleanup is now the primary cleanup focus at Y-12.

Initial planning for the MTF started in 2012 using money from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, also known as the “stimulus bill.” DOE officials consulted with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation. TDEC lists East Fork Poplar Creek on a list of impaired waterways, due in part to mercury contamination.

The goal of the MTF planning is to help reduce off-site migration, Darby said. Officials are trying to reach a target mercury concentration of 51 parts per trillion or less.

Darby said construction on the mercury treatment plant could be complete in 2021, according to current estimates. But it’s not clear how long the plant would operate.

“It will be operated as long as necessary to treat the mercury coming from the West End Mercury Area,” Darby said at a DOE Site Specific Advisory Board meeting on Wednesday. “There will come a time when we won’t need the treatment plant anymore.”

Darby said a public comment period for the MTF started in August and will end in October. After the public comment period, DOE will review the comments and then work with EPA and TDEC to establish a final “record of decision,” or ROD, which will select a final alternative.

The West End Mercury Area is near, but south of, the Highly Enriched Uranium Materials Facility and the proposed Uranium Processing Facility on the west side of Y-12.

Among the buildings mercury was used in at Y-12 are buildings known as Beta 4, Alpha 5, and Alpha 4, Darby said. It was in the basements and foundations and in soil around the buildings, and it got into the storm sewer system, where it mixes with groundwater and leaves the site.

Plans for the MTF presented Wednesday show a “headworks” facility at Outfall 200, which is just east of the West End Mercury Area, or WEMA. That facility would include the six- to seven-story stormwater holding tank.

The treatment plant would be a kilometer away on the east side of Y-12, closer to Scarboro Road. The mercury that separates out and settles as a stable compound could be disposed of at a landfill, possibly including one on Chestnut Ridge or at the Environmental Management Waste Management Facility west of Y-12.

Officials aren’t sure yet how much mercury they might obtain.

Claude Buttram, program manager for CH2M Hill, a subcontractor to UCOR, DOE’s cleanup contractor, said one to five rolloff bins per week could be produced. Each bin holds 20 cubic yards, he said.

Sue Cange, manager of DOE’s Oak Ridge Office of Environmental Management, said officials have agreed to use a modular approach with the MTF. They plan to operate it for up to two years to see if they can reach 51 parts per trillion. If not, they could change their approach, possibly adding another stage at the plant, or doing other things at Y-12, like stabilizing creek beds.

The MTF could cost $3.1 million per year to operate and maintain. A SSAB member raised a question about funding.

Cange’s response: As cleanup funding falls at the East Tennessee Technology Park, cleanup money for Y-12 should go up.

“We anticipate some level funding in that program,” Cange said.

A presentation by Darby to the SSAB said the proposed MTF would lead to immediate reductions in mercury releases from the West End Mercury Area storm sewer system to Upper East Fork Poplar Creek and make progress toward achieving compliance with regulatory criteria. It would also allow potential future mercury releases to be controlled when, for example, buildings where mercury was used are demolished.

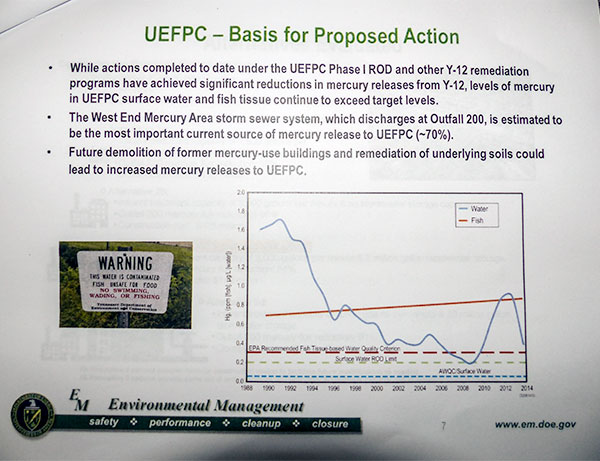

The ultimate goal is to eliminate current fish advisories and use restrictions on East Fork Poplar Creek.

Here is background information on mercury at Y-12, as reported in Darby’s presentation:

- Large quantities were used during the Cold War for nuclear weapons research and development from 1950 to 1963.

- An estimated 24 million pounds was brought to Y-12.

- More than two million pounds was spilled or lost, or officials haven’t been able to account for it.

- About 700,000 pounds was lost to the environment, including:

- Contamination in process buildings and soils—428,000 pounds

- Releases to Upper East Fork Poplar Creek—239,000 pounds

- Contamination in New Hope Pond sentiment—15,000 pounds

- Airborne releases—51,000 pounds

- That leaves about 1.3 million pounds that officials haven’t been able to account for.

Claude Buttram, left, program manager for cleanup subcontractor CH2M Hill, and Spencer Gross of the Oak Ridge Site Specific Advisory Board are pictured above. (Photo by John Huotari/Oak Ridge Today)

Mercury remediation has been under way at Y-12 since the 1980s. Some of the more recent projects have included a Big Spring Water Treatment System (2005), a WEMA storm sewer cleanup and relining (2009-2011), and Old Scrapyard cleanup (2009-2012). Darby’s presentation said the operating experience at Big Spring Water Treatment System to treat discharge from Outfall 51 and Building 9201-2 sumps has been very successful. Although there have been significant reductions in mercury releases from Y-12, the levels of mercury in surface water and fish tissue in Upper East Fork Poplar Creek “continue to exceed target levels,” Darby said.

At about 70 percent, the West End Mercury Area storm sewer system, which discharges at Outfall 200, is estimated to be the most important current source of mercury released to Upper East Fork Poplar Creek. And future demolition of former mercury-use buildings and remediation of the underlying soils could lead to increased mercury releases to the waterway.

Mercury contamination can cause brain and nervous system damage in people who eat contaminated fish.

In 2013, officials said demolition of four buildings that used mercury to separate lithium for nuclear weapons could start in 2021 on the Beta 4 building at the west side of the West End Mercury Area and then move east to Alpha 5 and Alpha 4. Another contaminated building, Alpha 2, will also be torn down, officials said at the time.

See Darby’s presentation here:Â Outfall-200-MTF_SSAB_Meeting_Presentation_090915.

More information will be added as it becomes available.

Copyright 2015 Oak Ridge Today. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed.

Leave a Reply