An aerial view of the Biology Complex at the Y-12 National Security Complex. Plans call for eventually demolishing the complex. (Photo courtesy U.S. Department of Energy)

The federal spending bill approved last week includes $639 million for the federal government’s cleanup program in Oak Ridge, including what could be full funding for a top priority deactivation and demolition project at the Y-12 National Security Complex.

The $639 million for the current fiscal year is an increase of $141 million or more, compared to recent fiscal years, and it’s the most money appropriated in a while.

Besides Y-12, the fiscal year 2018 funding will be used for U.S. Department of Energy cleanup projects at East Tennessee Technology Park (the former K-25 site) and Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

“It’s very positive for us,” said Jay Mullis, manager of the DOE Oak Ridge Office of Environmental Management, or OREM. Mullis gave a brief update at a meeting of the Oak Ridge Reservation Communities Alliance on Monday.

In addition to $125 million to deactivate and demolish the Biology Complex at Y-12, the fiscal year 2018 spending bill includes $17.1 million in funding for the planned Mercury Treatment Facility at Y-12, about $200 million for continued cleanup work at ETTP, and a total of roughly $12 million for the Environmental Management Disposal Facility, or EMDF. That’s a proposed landfill that could be west of Y-12 and accept waste from future cleanup work at Y-12 and ORNL, possibly early in the 2020s. The project plan for EMDF is expected to be open to public comment later this summer.

The $639 million in cleanup money appropriated for Oak Ridge last week is $125 million more than the $390 million the Trump administration had requested for fiscal year 2018, U.S. Senator Lamar Alexander, a Tennessee Republican, said in a press release last Wednesday

The difference is about what is required for the Biology Complex at Y-12, a top priority for the Oak Ridge cleanup program. The spending bill includes $125 million earmarked for that project, Mullis said. The deactivation work includes asbestos abatement.

DOE officials expect the Biology Complex deactivation and demolition work to cost $125 million over three to four years. That means the earmarked money is expected to be enough to complete the project. The cleanup program can carry over the funds, meaning it doesn’t have to spend all of the money this fiscal year, which ends September 30.

At ETTP, Mullis and Mike Koentop, executive officer in OREM, said cleanup funding remains constant at about $200 million. The site’s five large gaseous diffusion buildings, once used to enrich uranium for atomic weapons and commercial nuclear power plants, have been demolished, and cleanup work at ETTP is expected to be completed by 2020. But work continues on other buildings and facilities.

After cleanup work is completed at ETTP, it will shift to Y-12 and ORNL.

At Monday’s meeting, Mullis and Koentop said the fiscal year 2018 spending bill includes $17.1 million for another top priority for EM at Y-12, the Mercury Treatment Facility. That project, which broke ground in November, will eventually allow cleanup work and demolition of four large mercury-contaminated buildings and soil at Y-12, mostly on the west side of the 811-acre plant. Mercury was used to separate lithium for nuclear weapons at Y-12 during the Cold War.

The $17.1 million for the Mercury Treatment Facility can also be carried over past the current fiscal year, Koentop said. During the November groundbreaking ceremony, officials said the facility is expected to start operating in late 2022, although additional funding will be required.

Besides the money for the Biology Complex, ETTP, and Mercury Treatment Facility, the fiscal year 2018 spending bill also includes $2 million in operating funds that will support planning for the Environmental Management Disposal Facility. It could be west of Y-12 at a site known as 7C, or the Central Bear Creek Valley site. The EMDF will be used to support cleanup work at Y-12 and ORNL as the current landfill west of Y-12, called the Environmental Management Waste Management Facility, fills up as cleanup work concludes at ETTP.

The spending bill also includes $10 million for construction and design funding to continue making progress on the EMDF, Mullis and Koentop said.

In his press release, Alexander said he has made a personal commitment to increase funding for the cleanup of hazardous materials and facilities at Cold War-era sites in Oak Ridge.

“This bill accelerates cleanup of hazardous materials and facilities at the East Tennessee Technology Park, the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, and the Y-12 National Security Complex,” the senator said. “The funding supports vital investments in a new mercury treatment facility—also known as Outfall 200—which will help reduce the amount of mercury getting into Tennessee waterways to safe levels and make it possible for cleanup work at Y-12 to continue, which supports thousands of jobs.”

Alexander spoke at the groundbreaking of the Mercury Treatment Facility in November.

OREM is still going though the fiscal year 2018 spending bill to determine exactly what’s in it. Any additional money could be used for continued risk reductions at excess contaminated facilities at ORNL and Y-12, officials said.

The highest priority at ORNL that is not part of risk reduction efforts is the continued disposition of uranium-233.

The three Oak Ridge sites were built to help make the world’s first atomic weapons as part of the top-secret Manhattan Project during World War II, and Oak Ridge sites continued to be involved in nuclear weapons work, uranium enrichment, and scientific research, sometimes involving radiological materials, after the war.

The planned Mercury Treatment Facility at the Y-12 National Security Complex in Oak Ridge. (Image courtesy UCOR/U.S. Department of Energy Oak Ridge Office of Environmental Management)

Excess facilities, Biology Complex

Officials said the work that has already been done on environmental management, or EM, projects has put Oak Ridge in a good position for additional funding. They have used money available in previous fiscal years—in fiscal year 2017, there was about $26 million or so available—for excess facilities and hazard abatements at ORNL and Y-12. Examples of the work have included mercury abatement of the COLEX, or column exchange, equipment outside the Alpha 4 building, one of the mercury-contaminated buildings on the west end of Y-12. More than two tons of elemental mercury have been removed, Mullis said Monday.

The excess facilities work has also included asbestos abatement at Building 7500, also known as the Homogenous Reactor Experiment facility at ORNL.

The excess facilities work has continued into the current fiscal year, fiscal year 2018, under a continuing resolution, which generally holds federal funding at previous levels. The federal government had operated under continuing resolutions until the spending bill was approved last week.

DOE has said Oak Ridge is home to more higher-risk excess contaminated facilities than any other U.S. Department of Energy site in the nation. As of December 2016, Oak Ridge had 60 of DOE’s inventory of 203 higher-risk excess facilities.

But this month, DOE said recent demolition projects are helping to change that. Two small buildings have been removed at the Biology Complex, OREM said earlier this month. On Monday, Mullis and Koentop said excess facilities money was used for that project.

Even with those demolitions, though, six buildings remain at the Biology Complex. The goal is to complete demolition at the complex in the early 2020s.

Crew members prepare samples for shipment to the laboratory for analysis from inside the Biology Complex at Y-12 National Security Complex. (Photo courtesy U.S. Department of Energy)

The Biology Complex once consisted of 12 buildings, but four of them were demolished in 2010 as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, the stimulus package signed into law by President Barack Obama early in his presidency.

Now vacant, the Biology Complex was originally built to recover uranium from process streams. It later housed DOE’s research on the genetic effects of radiation from the late 1940s. It once housed more individuals with doctorates than anywhere in the world, according to the U.S. Department of Energy. DOE has said the men and women who worked there radically enhanced the world’s knowledge in biology, including the discovery of the Y chromosome.

In April, the Oak Ridge Office of Environmental Management and its cleanup contractor, URS | CH2M, or UCOR, finished characterizing the Biology Complex, identifying contaminants before demolishing and disposing of the buildings. DOE has said it was crucial to get crews into the complex before the working environment became too hazardous. Examples of hazards have included a failed roof, fallen exterior tiles, and asbestos and other risks due to roof leaks.

Last year, OREM said the Biology Complex would be a top priority if excess funding were available, and there was the possibility that some additional money could be available. That’s because the budget request submitted to Congress by President Donald Trump in May 2017 included $225 million for high-risk excess contaminated facilities at Y-12 and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California. But it wasn’t clear how much of that money might have been used in Oak Ridge, if the president’s budget request had been approved. It also wasn’t clear how much of it might have been used specifically for the Biology Complex. But some portion of that $225 million would have been in addition to the $390 million requested by the Trump administration for cleanup work in Oak Ridge in fiscal year 2018, the current fiscal year.

However, the spending bill approved by Congress and signed by Trump last week has different spending levels than had either been requested by the Trump administration or approved in legislation in the House and Senate. (You can see some information on those different proposed spending levels in this story.)

Funding history

The $639 million in funding for the EM program in Oak Ridge in fiscal year 2018, the current fiscal year, is an increase of about $141 million, compared to the $498 million appropriated in fiscal year 2017, which ended September 30.

This year’s funding is also higher than the $431 million appropriated in fiscal year 2015 and the $469 million in fiscal year 2016.

It’s not clear how long it’s been since Oak Ridge has had in the range of more than $600 million in environmental management funding. DOE officials said it’s probably the most in at least 15 years.

Oak Ridge has previously received large amounts of money for cleanup work at federal sites. In May 2014, the Oak Ridge Office of Environmental Management announced that it had completed field work on 27 cleanup projects at the three major federal sites using $751 million in Recovery Act funds. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, also known as the Recovery Act or stimulus bill, was passed by Congress and signed by Obama in February 2009. It was meant to help stimulate an economic recovery during the depths of the Great Recession, and it was intended to address long-neglected infrastructure projects and programs. In Oak Ridge, the Recovery Act funding paid for several demolition projects such as the demolition of the 1.4-million-square-foot K-33 Building at the East Tennessee Technology Park and other projects ranging from mercury reduction at Y-12 to transuranic waste processing at ORNL.

Two legislators approve, one opposed

Last week, Alexander and Representative Chuck Fleischmann voted for the spending bill approved by Congress, while Senator Bob Corker, a Tennessee Republican who is not seeking re-election in November, opposed it. Alexander is chair of the Senate Energy and Water Development Appropriations Subcommittee. Fleischmann, a Tennessee Republican whose district includes Oak Ridge, is vice chair of the House Energy and Water Subcommittee.

Alexander cited record funding for the third consecutive year for the DOE Office of Science—ORNL is an Office of Science lab—and increased funding for supercomputing and environmental cleanup in Oak Ridge. The spending bill includes new funding for advanced manufacturing; $663 million for the Uranium Processing Facility at Y-12, one of the largest construction projects in the country; and record funding of $14.7 billion for the National Nuclear Security Administration, Alexander said. Y-12 is an NNSA site.

Fleischmann said he voted for the bill, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, because of increased defense funding, the largest in 15 years, and to end continuing resolutions that “have hampered the progress of our nation.” H.R. 1625, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, passed the House in a 256-167 vote.

The spending bill substantially benefits Tennessee’s Third District, which includes Oak Ridge, Fleischmann said. Among the benefits are $4 billion for treatment, prevention, and local law enforcement as the nation battles the opioid crisis, a “national emergency,” and full funding for the Chickamauga Lock project near Chattanooga, Fleischmann said.

But Corker, a member of the Senate Budget Committee, slammed the spending bill. He called the 2,232-page bill one of the most “grotesque” pieces of legislation he can remember, and he raised concerns about the nation’s fiscal issues, including its deficits and $21 trillion worth of debt—and what he said are $100 trillion in unfunded liabilities. The spending bill will add a minimum of $2 trillion in deficits during the next 10 years, Corker said.

“I’m discouraged,” Corker said in a speech on the Senate floor. “I’m discouraged about where we are today. I’m discouraged about the fact that we continue to be engaged in generational theft, my generation…We won’t deal with mandatory spending, mandatory spending that benefits my generation. To these young people sitting in front of me: we’re engaged right now in generational theft because we are transferring from you, to us, your future resources because we don’t have the courage or the will to deal with issues…When we pass this bill, your standard of living will be diminished when you go on to college and graduate and start working in your jobs. Just know that what we’re getting ready to do tonight or tomorrow is going to diminish your standard of living because we’re going to pass a huge bill, unpaid for, that you’re going to pay for and your children are going to pay for.”

The East Tennessee Technology Park, the former K-25 site in west Oak Ridge, is pictured above. It is being cleaned up and converted into a private industrial park. UCOR, or URS | CH2M Oak Ridge LLC, is the U.S. Department of Energy’s cleanup contractor for the DOE Oak Ridge Reservation, and it is primarily focused on ETTP cleanup. (Photo by UCOR)

Besides concerns about spending, deficits, and the national debt, critics also said members of Congress hadn’t had time to read the bill before they were asked to vote on it last week. That was one of the concerns raised by Trump when he briefly threatened to veto the bill, which would have shut down the government, on Friday. But the president, who raised other issues as well, including the fact that it didn’t fully fund his proposed border wall, relented and signed the legislation Friday afternoon. However, he vowed not to sign a bill like it again.

Before the president signed the bill, the House approved it Thursday, March 22, and the Senate approved it early Friday, March 23.

Alexander said of the spending bill: “This funding for our national defense, national parks, national laboratories, and the National Institutes of Health is within the new budget spending caps and grows at about the rate of inflation. The federal debt problem, which is the real problem, is the result of runaway federal entitlement spending, which is not part of this funding bill.”

Here’s a look at the president’s budget requests and actual enacted spending levels during the past four fiscal years:

Fiscal Year 2015

- President’s request—$385 million

- Enacted—$431.2 million

Fiscal Year 2016

- President’s request—$365.7 million

- Enacted—$469.2 million

Fiscal Year 2017

- President’s request—$391.4 million

- Enacted—$498.3 million

Fiscal Year 2018

- President’s request—$390.2 million

- Enacted—$639.8 million

Here is an earlier summary of Oak Ridge Environmental Manangement funding:

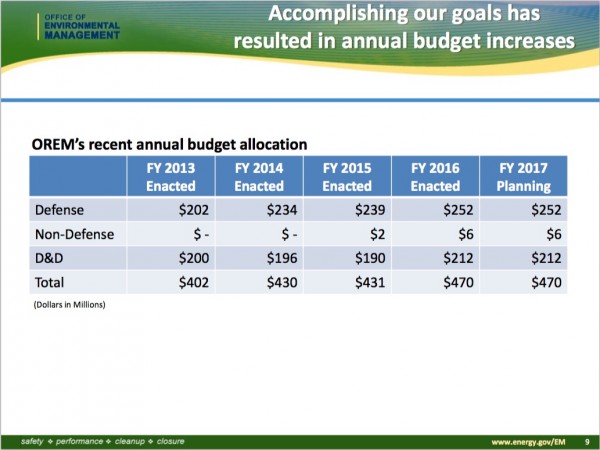

A funding chart for the U.S. Department of Energy Oak Ridge Office of Environmental Management, as presented during a community budget workshop on April 12, 2017. (Image courtesy US DOE/Oak Ridge Office)

See previous stories on the Biology Complex at Y-12 here and here.

See our previous story on the Mercury Treatment Facility at Y-12 here.

See an earlier story on the president’s budget request for EM in Oak Ridge for fiscal year 2018 here.

See stories on high-risk excess facilities here and here.

More information will be added as it becomes available.

Do you appreciate this story or our work in general? If so, please consider a monthly subscription to Oak Ridge Today. See our Subscribe page here. Thank you for reading Oak Ridge Today.

Copyright 2018 Oak Ridge Today. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed.

Leave a Reply