Note: This story was updated at 9:45 a.m. June 11.

More than 1,000 people marched and protested in Oak Ridge last week, asking for equal treatment for black people.

They said the nation is obligated to fight systemic racism, racial inequality, and police brutality. They want to live without fear. They advocated for police reforms, accountability, and the use of de-escalation tactics.

Protesters hope to end 400 years of oppression that started with slavery in America in 1619 and continued after the Civil War with attacks on black people, lynchings, the Ku Klux Klan, segregation, discrimination, and racism. That oppression has been felt in Oak Ridge, and some young adults and teenagers said they have experienced or witnessed racism.

Protesters said they were angry, upset, and frustrated. They called the death of George Floyd while he was detained by police in Minneapolis last month a murder. They recalled the deaths of other black men and boys, some killed by police and others by citizens. They acknowledged that there are many good police officers, but they condemned police officers who they said hide behind their badges to do wicked deeds.

“Enough is enough,” protesters said. “We are done dying.”

Protesters met at Oak Ridge High School Tuesday afternoon, June 2, and marched to the Oak Ridge Civic Center. They carried signs and wore T-shirts that said “Black Lives Matter” and “I can’t breathe.” They chanted “No justice, no peace” and, led by organizer Trevor King, “Make racism illegal.” Silence is compliance, the protesters said, and silence in the face of evil is itself evil.

They said racism still exists in America, including in health care, job hiring practices, and in who is pulled over by police and who is charged.

They said they want America to live up to its values, its promise of liberty and justice for all. They cited this foundational line from the Declaration of Independence:

“We hold these Truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.”

The Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776

“This to me means everyone should have the right to live in this country without fear,” said Stephen Barnes, one of the speakers featured at the protest.

They aren’t asking for black lives to matter more, the protesters said. They just want black lives to matter as much.

They asked people to not use stereotypes. They said it is important to acknowledge that racism is a problem, and they pointed out the value of white people apologizing.

They said they want to be included.

“We just want to be heard, accepted, cared about,” speaker Don Colquitt said.

More than 1,200 people attended the Tuesday protest. Some were critical of what they said is a lack of leadership from President Donald Trump.

The Tuesday protest in Oak Ridge was one of hundreds across the country these past few weeks after George Floyd, a 46-year-old black man, died in Minneapolis on May 25 as a white police officer kneeled on his neck for eight minutes and 46 seconds as two other officers held Floyd down. Police had responded to a call about a counterfeit $20 bill.

The white police officer who held Floyd down, Derek Chauvin, 44, has been charged with second-degree murder, third-degree murder, and second-degree manslaughter. Three other officers at the scene, including the other two holding Floyd down, have been charged with aiding and abetting in Floyd’s death: J. Kueng, Thomas Lane, and Tou Thao. All four have been fired from the Minneapolis Police Department.

As he lay dying, Floyd told police that he couldn’t breathe.

Pastor Henry Watson of Mount Zion Baptist Church in Oak Ridge called it a senseless murder. Some officers will hide behind their badge and do wicked deeds, Watson said.

“The only way that this can be stopped is for our voices to be heard,” he said.

Pastor Derrick Hammond of Oak Valley Baptist Church, who is black and an Oak Ridge City Council member, also called it a murder, although he said he hasn’t been able to watch the video.

Floyd’s death was a flashpoint, Hammond said during a small group discussion about race on Tuesday morning. Thousands of white people have marched and protested with thousands of black people since Floyd’s death.

Hammond said white America has been able to justify the deaths of other black men and boys with dismissals like “Well, he was a thug,” or “Well, he shouldn’t have done that.”

But every once in a while, there is a death that can’t be justified, and it shocks the white conscience, Hammond said.

“In many ways, (the death of) George Floyd was so horrific that it shocked the white conscience,” Hammond said.

Oak Ridge Police Chief Robin Smith could not explain what Minneapolis police officers were doing in the video of Floyd’s death. The police officers’ actions do not comport with what the Oak Ridge Police Department practices or teaches, Smith said.

“That’s not how we do it,” he said.

In Oak Ridge, police officers will move a detained person up into what is called a rescue position once the person is under control, Smith said.

Smith, who said he became a police officer because he wanted to protect people from bullies, could not explain why the three officers with Chauvin did not intervene. Either they condoned what Chauvin was doing and thought it was appropriate, or they did not feel it was safe for them to “speak up,” Smith said.

Smith said he wants ORPD officers to feel safe to “speak up” when they see something that is not appropriate. It has to be safe for the community to address problems as well, Smith said.

Protesters on Tuesday offered hope that Americans can change, and they were encouraged by the large, diverse turnout. But racism needs to be acknowledged, said King, the protest organizer.

“Everyone just needs to become a good person,” he said.

But if you’re truly serious about “moving forward,” you will be made uncomfortable, Hammond said.

He said white people have asked him, since Floyd’s death, what they can do.

He said white people have to redefine what they consider murder. It’s not just the unlawful killing of someone, he said. It’s the biblical definition—the killing of an innocent person. If the killing of George Floyd is murder, then the killing of Trayvon Martin, 17, by former neighborhood watch captain George Zimmerman in Florida in 2012 is also murder, Hammond said.

“For a black person, all of them look like this,” he said. “It’s all murder.”

White people have to confront their own hypocrisy, Hammond said.

If white people want black people to think not all whites are racist and not all police are bad, then white people have to accept that not all blacks are thugs or criminals, not all Muslims are terrorists, and not all immigrants are illegal, Hammond said.

He said those who want to support justice for George Floyd have to kneel with Colin Kaepernick as well.

Kaepernick is an NFL quarterback who kneeled during the national anthem in 2016 to peacefully protest social injustice and police brutality in America. That made white people uncomfortable, Hammond said. Kaepernick played for the San Francisco 49ers, but he split with them the following March and has been unable to play in the league since then.

The protest led by Kaepernick has been criticized by Trump.

Hammond said people did not do enough to learn why Kaepernick was kneeling.

“You cannot stand with us in regards to George Floyd and refuse to kneel with Colin Kaepernick,” Hammond said.

Hammond said there is much work to be done, and Tuesday’s protest has to be a movement, not a moment.

“This is the beginning,” he said.

Besides Hammond, three other City Council members, as well as two Oak Ridge police officers, marched with protesters from the High School to the Civic Center last week, although the march and protest were not organized by the city.

Oak Ridge Mayor Warren Gooch, one of those City Council members, said the Book of Isaiah instructs Christians to “stop doing wrong; learn to do right; seek justice; and encourage the oppressed.”

The city condemned racism, bigotry, discrimination, hatred, and violence in September 2017. That condemnation followed a deadly white nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. The city reaffirmed equal rights for all, and it condemned all actions that violate fundamental rights delineated in the Declaration of Independence, guaranteed by the United States Constitution, and incorporated in the Oak Ridge City Charter, Gooch said.

Last week’s march began at Oak Ridge High School. That was appropriate, Gooch said, because 65 years ago the school became one of the first integrated high schools in the South.

Oak Ridge police officers were welcomed and thanked at Tuesday’s protest, including by Gooch and Hammond. Led by Hammond, ministers prayed for the police officers.

King, the protest organizer, said Oak Ridge proved that protests can be done peacefully. There were two counter-protesters, but protesters surrounded them and hid their counter-protest signs with protest signs. Eventually, the counter-protesters left. They carried signs that said “White safety matters” and “Black crimes matter.” One wore a red Trump campaign hat that said “Make America great again.”

Organizers worked to ensure that the counter-protest didn’t become a distraction.

Slavery, segregation

The history of oppression in Oak Ridge and the area that is now Oak Ridge dates back almost 200 years or more.

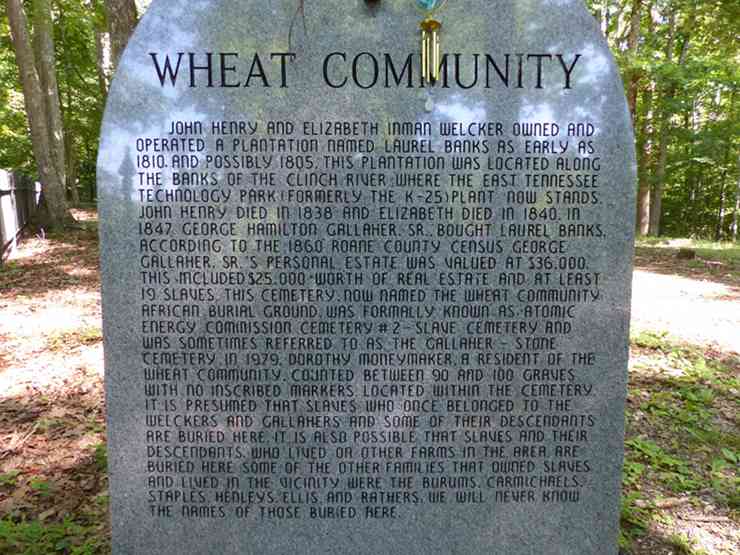

In the 1800s, there was a plantation named Laurel Banks along the Clinch River in what is now west Oak Ridge, according to a memorial marker at the African Burial Ground in the former Wheat community. The plantation was in operation as early as 1810, and possibly 1805. It was where the East Tennessee Technology Park (the former K-25 site) is now. The plantation was owned and operated by John Henry and Elizabeth Inman Welcker until they died in 1838 and 1840.

In 1847, George Hamilton Gallaher Sr. bought Laurel Banks.

By 1860, his estate was valued at $36,000, according to the Roane County Census. The estate included $25,000 worth of real estate and at least 19 slaves, according to the memorial marker.

The African Burial Ground, which has been referred to as a slave cemetery and the Gallaher-Stone Cemetery, may have between 90 and 100 graves, and they are presumed to have been the burial places for enslaved people. The graves do not have inscribed markers. Today, some are marked with stones.

“It is presumed that slaves who once belonged to the Welckers and Gallahers and some of their descendants are buried here,” the memorial marker said. “It is also possible that slaves and their descendants who live on other farms in the area are buried here. Some of the other families that owned slaves and lived in the vicinity were the Burums, Carmichaels, Staples, Henleys, Ellis, and Rathers. We will never know the names of those buried here.”

Decades later, the Wheat community and others in the area were displaced by the city that is now Oak Ridge. It was built to help produce atomic bombs as part of the top-secret Manhattan Project during World War II.

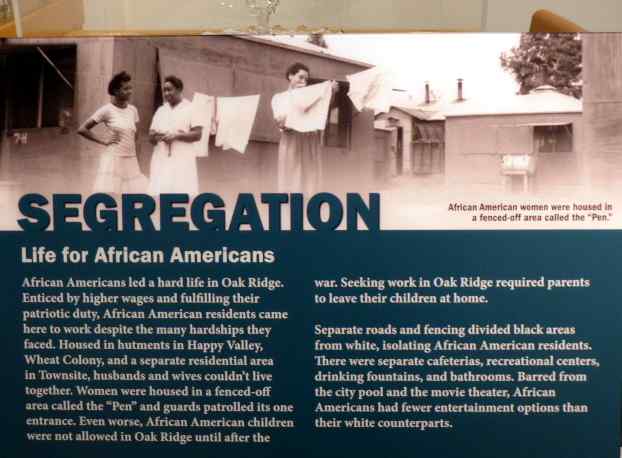

African Americans were segregated in Oak Ridge, and life was difficult for them, according to a display about segregation at the U.S. Department of Energy’s new K-25 History Museum. They were housed in hutments in Happy Valley, Wheat Colony, and a separate residential area in Townsite. Husbands and wives couldn’t live together, the history display said. Women were housed in a fenced-off area called the “Pen,” and guards patrolled its one entrance.

“Even worse, African American children were not allowed in Oak Ridge until after the war,” the display said. “Seeking work in Oak Ridge required parents to leave their children at home.”

There were separate roads and fencing that divided black areas from white, which isolated African American residents, the display said. There were also separate cafeterias, recreational centers, drinking fountains, and bathrooms. African Americans were barred from the city pool and the movie theater, and they had fewer entertainment options than their white counterparts, the history display said.

Life has changed, including after slavery ended with the Civil War and the 13th Amendment in 1865, and after school desegregation in the 1950s and the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s. But racism continues. Four young adults and teenagers at the Tuesday morning discussion about race said they have experienced or witnessed racism, including at Oak Ridge High School and at East Tennessee State University. In one case, a young woman said an administrator was dismissive of racist behavior toward her during her sophomore year at ORHS. She said she documented and reported the racist behavior, but an administrator said “Oh, he didn’t mean that,” and an apology from her male classmate seemed coerced.

Asked about potential solutions, King said people should change themselves and have conversations. Be a good person, and do the right thing, King said.

“All we need is for you to simply acknowledge that there is a problem,” he said.

See a Facebook video of most of last week’s protest at the Oak Ridge Civic Center by Kayla Boone here.

Leave a Reply