Ray Smith, Y-12 National Security Complex historian and city historian, announces a book published posthumously that was written by Bill Wilcox, a former city historian, former technical director at K-25 and Y-12, and a passionate advocate for historic preservation, including of the former K-25 site. Smith announced the book at a ceremony unveiling plans for a K-25 History Center on the second floor of the city-owned fire station at K-25, now known as East Tennessee Technology Park, on Thursday, Oct. 19, 2017. (Photo by John Huotari/Oak Ridge Today)

He was a passionate advocate for preserving Oak RidgeŌĆÖs history.

He was known for his bow ties and captivating storytelling. He once led the effort to save the former K-25 Building in west Oak Ridge, or at least part of it.

Now the legacy of Bill Wilcox will live on at the K-25 History Center.

Construction on the history center could start early next year on the second floor of Oak Ridge Fire Station Number Four. That fire station, previously transferred to the city, is on the south side of the former K-25 Building at East Tennessee Technology Park in west Oak Ridge.

Officials preparing for the construction of the history center gave tours of its future home at the fire station on Thursday. The tours followed a lunchtime celebration that featured tributes to Wilcox and included speeches and presentations by U.S. Department of Energy and Oak Ridge officials, and federal contractors and historic preservation advocates. Wilcox was hailed as the ŌĆ£father of K-25 historic preservation.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£He would have been really proud,ŌĆØ said Ray Smith, WilcoxŌĆÖs friend and Y-12 National Security Complex historian and city historian. ŌĆ£His legacy lives on.ŌĆØ

The history center was called for in a 2012 agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy and other parties. That agreement, made as part of the National Historic Preservation Act, allowed the complete demolition of the four-story, 44-acre K-25 Building.

The agreement allowed workers to demolish the North Tower at the K-25 Building, which historic preservationists had lobbied for years to save.┬ĀIn exchange for the complete demolition of K-25, the agreement called for the history center at the fire station, a K-25 replica equipment building and viewing tower, an┬Āonline virtual museum,┬Āand a $500,000 grant to buy and stabilize the historic Alexander Inn in central Oak Ridge, which has since been┬Āconverted into an assisted living center.

“We have made a substantial investment to ensure future generations can hear and understand the amazing story behind the men and women who constructed and operated the former K-25 site,” said Jay Mullis,┬Āacting manager of DOEŌĆÖs Oak Ridge Office of Environmental Management, which is overseeing ETTP site cleanup.

Mullis said the discussions of preserving K-25ŌĆÖs history go back about 15 years. There was a decade of sometimes-contentious talks before the 2012 agreement, he said.

DOE and its partners understand the historical significance of the site, Mullis said.

Construction on the three facilities to preserve K-25ŌĆśs historyŌĆöthe History Center, the Equipment Building, and the Viewing TowerŌĆöshould start in 2018 and be complete in 2019, Mullis said.

The K-25 Building was a mile-long U-shaped structure that was once the worldŌĆÖs largest building under one roof. It was built to help enrich uranium during World War II as part of the top-secret Manhattan Project, a federal program that made the worldŌĆÖs first atomic weapons.

But K-25ŌĆśs major contribution was during the Cold War, when the plant enriched uranium-235 for nuclear defense, Wilcox said in a recorded interview played during Thursday’s lunchtime ceremony.

ŌĆ£K-25 just has a long, rich history,ŌĆØ Wilcox said in that recorded interview.

He said the United States could not have won the Cold War without K-25. Also, among other accomplishments, centrifuge research conducted at K-25 helped with the development of the polio vaccine, Wilcox said.

Now demolished, the former mile-long, U-shaped K-25 Building, pictured above, was once used to enrich uranium for atomic weapons and commercial nuclear power plants. Located in west Oak Ridge, the site’s “footprint,” its concrete slab, is part of the Manhattan Project National Historical Park. There is a separate effort to preserve the site’s history; that work could be incorporated into the new park. (Photo courtesy of U.S. Department of Energy)

After K-25, there were four more large buildings at ETTPŌĆöK-27, K-29, K-31, and K-33ŌĆöthat also helped enrich uranium for atomic weapons and commercial nuclear power plants through a process known as gaseous diffusion. But uranium enrichment operations at the site ended in 1985, and all five gaseous diffusion buildings have now been torn down, with the demolition of the last one, K-27, completed in August 2016.

The site is now being cleaned up and converted into an industrial park.

The three history-related structures at the former K-25 site, which is also known as Heritage Center, will have three missions.┬ĀThe History Center will tell the story of the workers. The three-story Equipment Building will mimic the exterior of the K-25 Building and focus on the plantŌĆÖs technology and include gaseous diffusion equipment replicas. The Viewing Tower will be 70 feet high and show visitors the size of the site with an observation deck that will have a 360-degree view that will include Happy Valley, a former K-25 construction camp that was once home to 15,000 people on the other side of State Route 58. All three history facilities┬Āwill be on the south side of the former K-25 Building and in or near the cityŌĆÖs fire station.

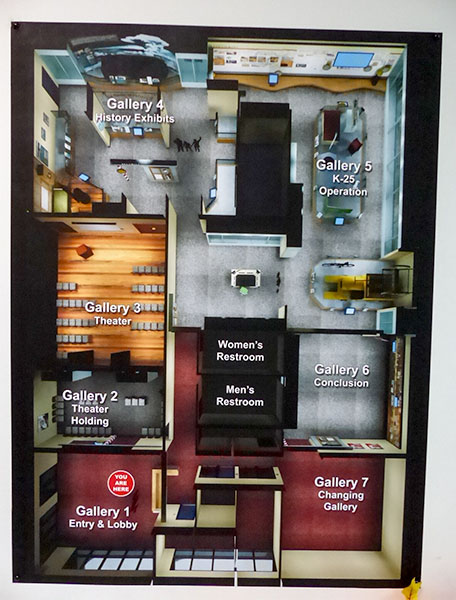

The history center, the subject of ThursdayŌĆÖs tours, will be 7,500 square feet, and it will include exhibits, a theater, oral histories, and a few hundred artifacts. Artifacts on display on Thursday included a bicycle that workers once used to get around the large gaseous diffusion buildings, which were up to a mile long end-to-end. Also on display were an aluminum construction hard hat, customized dies used to stamp identifying numbers onto metals parts and equipment, a light switch cover that included a security reminder to lock secret files before leaving an office, and a laboratory timer. There was also a phone and directory, and a clarion horn that was part of the alarm system to alert workers when radiation had been released.

Artifact curator Steve Goodpasture, an environmental scientist for UCOR, the U.S. Department of Energy’s cleanup contractor in Oak Ridge, shows the plans for the K-25 History Center, an Equipment Building, and Viewing Tower during a tour of the future home of the history center on the second floor of Oak Ridge Fire Station Number Four at East Tennessee Technology Park on Thursday, Oct. 19, 2017. (Photo by John Huotari/Oak Ridge Today)

Artifact curator Steve Goodpasture said a K-25 history book by Wilcox that has just been published posthumously has been used to help develop the history center, which will be open to the public. Goodpasture is an environmental scientist for UCOR, DOEŌĆÖs cleanup contractor in Oak Ridge.

ŌĆ£His fingerprints are all over this,ŌĆØ Goodpasture said of WilcoxŌĆÖs influence on the history center.

Wilcox was a chemist who started working at Y-12 during World War II as part of the┬ĀManhattan Project. He went on to become a technical director for Y-12 and K-25. Wilcox, who had moved to Oak Ridge from Rochester, New York, during the war, had worked at both sites. He oversaw development activities at both plants for many years, and he retired as a special assistant to the president of the contractor running the Oak Ridge sites and others.

WilcoxŌĆÖs passion for preserving Oak RidgeŌĆÖs historyŌĆöhe was the Oak Ridge city historian and he formed the Partnership for K-25 PreservationŌĆöhad a particular emphasis on the production plants.

ŌĆ£He was the undisputed leader of trying to save K-25,ŌĆØ said longtime friend Gordon Fee after Wilcox died in 2013. Fee is a retired president of Lockheed Martin Energy Systems, which used to operate all three Oak Ridge plantsŌĆöK-25, Y-12, and Oak Ridge National LaboratoryŌĆöas well as sites in Paducah, Kentucky, and Portsmouth, Ohio.

When the proposal to save K-25ŌĆÖs North Tower became impractical because of the high cost and the deteriorated condition of the building, Wilcox and others worked with the U.S. Department of Energy to come up with an alternative. The plan to build the exhibit space at K-25 is really due to WilcoxŌĆÖs leadership, said Fee, who was hired by Wilcox at K-25 in 1956. (Wilcox was then head of the physics department of the Gaseous Diffusion Plant at K-25, and Fee was hired as a junior physicist.)

But Wilcox also helped in other ways, including with the installation of historical monuments in front of the Oak Ridge Municipal Building; in the fight to preserve the Alexander Inn, which is now an assisted living center called the Alexander Guest House; and by serving as a guide on public bus tours of the K-25 site.

ŌĆ£No one worked harder for telling the K-25 story than Bill Wilcox,ŌĆØ said Mick Wiest of the Oak Ridge Heritage and Preservation Association.

The historic preservation work at K-25 is expected to cost about $20 million total. That work will be done by DOE and its contractors.┬ĀA bill approved by the Senate Appropriations Committee in July recommended $8 million for DOE for K-25 historic preservation work.

The lunchtime event on Thursday included a license signing ceremony that allows UCOR to start construction of the history center at the city-owned fire station.

ŌĆ£This project will help preserve the history of one of the most significant facilities in modern times,ŌĆØ Oak Ridge Mayor Warren Gooch said. ŌĆ£But more importantly, as we celebrate the 75th anniversary of our community, it is a tribute to the men and women whose work shaped the outcome of World War II and the Cold War.ŌĆØ

Oak Ridge Mayor Warren Gooch, seated at right, and UCOR President and Project Manager Ken Rueter, also seated, sign a license that allows UCOR, the federal cleanup contractor in Oak Ridge, to start construction of the K-25 History Center on the second floor of the city-owned Fire Station Number Four at East Tennessee Technology Park on Thursday, Oct. 19, 2017. Also pictured standing is Jay Mullis, acting manager of the U.S. Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge Office of Environmental Management. (Photo by John Huotari/Oak Ridge Today)

Other speakers paid tribute to wartime sacrifices and the first-of-its-kind technology at K-25 that helped end one war and prevented others.

ŌĆ£We never want to forget,ŌĆØ Wiest said.

He said K-25 was the largest single industrial project in world history.

Officials stressed that K-25ŌĆÖs history is a heritage tourism asset, and they said itŌĆÖs the most significant historical resource in Tennessee.

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs also an international resource,ŌĆØ Smith said. ŌĆ£What has happened here has impacted the entire world.ŌĆØ

Ken Rueter, UCOR president and project manager, said the secret work conducted at K-25 secured world peace in one of America’s most challenging eras, a “perilous time.”

“These facilities will preserve and celebrate that history,” Rueter said.

In an engineering and construction feat that seems impossible today, K-25 was built in 18 months, even as development continued on gaseous diffusion technology and finding a barrier to separate uranium-235 from uranium-238. More than 25,000 construction workers helped build the plant.

The four-story K-25 Building had about 3,000 converters, plus roughly 6,000 compressors and motors. Uranium hexafluoride used at the site was very corrosive, so everything had to be coated with nickel, or aluminum or copper, Goodpasture said. K-25 made its own ŌĆ£dry airŌĆØ for pneumatic equipment operations.

The K-25 gaseous diffusion plant cost about $500 million to build in 1944 dollars, Smith said. ThatŌĆÖs estimated to be roughly equivalent to about $8 billion in 2012 dollars, according to The Nuclear Secrecy Blog.

Most of the uranium used in “Little Boy,” the first atomic bomb used in wartime, was enriched at Y-12, and all of it was processed at Y-12. But near the end of World War II, some of the enriched uranium came┬Āfrom K-25 and S-50, a thermal diffusion plant west of K-25, before being fed into beta calutrons at Y-12, which used electromagnetic separation to enrich uranium. ŌĆ£Little BoyŌĆØ was dropped over Hiroshima, Japan, on August 6, 1945, shortly before the end of the war.

During Thursday’s ceremony, Smith presented WilcoxŌĆÖs book, ŌĆ£K-25: A Brief History of the Manhattan ProjectŌĆÖs ŌĆśBiggestŌĆÖ Secret.ŌĆØ ItŌĆÖs illustrated with photos by Ed Westcott, the official government photographer in Oak Ridge during World War II. The book is an expanded version of a series of 18 articles written by Wilcox and published in the former Oak Ridge Observer newspaper.

ŌĆ£He was literally working on it (the book) up until the day before he died,ŌĆØ Smith said.

The book has been published with help from WilcoxŌĆÖs family members, Smith, and the Oak Ridge Heritage and Preservation Association.

Oak Ridge, which was once known as Clinton Engineer Works, was the main production site for the Manhattan Project, and it included the┬Āthree major federal sites:┬ĀK-25; X-10, now Oak Ridge National Laboratory; and Y-12, now the Y-12 National Security Complex.

Besides the uranium enrichment facilities at K-25 and Y-12, the pilot facility for plutonium production was built at the Graphite Reactor at┬ĀORNL. Plutonium from the Manhattan Project site in Hanford, Washington, fueled the second atomic bomb, “Fat Man,” which was dropped over Nagasaki, Japan, on August 9, 1945.

Hanford and Oak Ridge are now both part of the Manhattan Project National Historical Park, which was established in November 2015. So is Los Alamos, New Mexico.

The national park includes the original K-25 footprint, the concrete slab on which the large building once stood. The national park work is separate from the K-25 historic preservation work, but the two efforts complement each other.

Gooch has previously cited the scientific advances that came about because of the Manhattan Project. He said they ŌĆ£literally changed the world.ŌĆØ Those accomplishments include┬Āthe first medical isotopes produced in 1946, the essential contributions made over the years in space exploration, the continuing research in nuclear science and energy, todayŌĆÖs high performance computing with the countryŌĆÖs most powerful computer for open science, and global leadership in advanced materials research.

The unveiling of the history center plans on Thursday was the fourth event in the city’s celebration of its 75th anniversary.┬ĀThe Oak Ridge site, about 59,000 acres, was selected for the Manhattan Project on September 19, 1942, and the city quickly grew to a wartime population of 75,000. Anniversary events are expected to continue into next year.

More information will be added as it┬Ābecomes available.

The layout of the K-25 History Center on the second floor of Oak Ridge Fire Station Number Four at East Tennessee Technology Park is pictured above on Thursday, Oct. 19, 2017. (Photo by John Huotari/Oak Ridge Today)

An image showing what the K-25 History Center could look like on the second floor of the city-owned fire station at East Tennessee Technology Park. (Graphic by David Brown/U.S. Department of Energy)

An image showing the K-25 History Center on the second floor of the city-owned fire station, right, at East Tennessee Technology Park, with the Equipment Building and Viewing Tower at left. (Graphic by David Brown/U.S. Department of Energy)

See our previous stories on┬Āthe K-25 History Center here.

See more photos here.

Do you appreciate this story or our work in general? If so, please consider a monthly subscription to Oak Ridge Today. See our Subscribe page here. Thank you for reading Oak Ridge Today.

Copyright 2017 Oak Ridge Today.┬ĀAll rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed.

Leave a Reply