CLINTON—Civil rights pioneer Anna Theresser Caswell asked people to not hate.

Civil rights leader Reverend Harold Middlebrook told local Black Lives Matters protesters that the movement will require more than a march.

Caswell and Middlebrook were two of about a dozen speakers at a Black Lives Matter march and protest that started at the Clinton football field and ended at Clinton Middle School on Thursday. Several hundred people attended.

Clinton Middle School is where the high school used to be. It was desegregated more than 60 years ago. It’s reported to have been the first high school in the South to desegregate under the U.S. Supreme Court decision Brown vs. Board of Education in 1954.

Caswell, 77, was one of the 12 Black teenagers who walked down from Green McAdoo School on Foley Hill and desegregated the old Clinton High School, which had been all-white, on August 27, 1956.

On Thursday, Caswell, who rode in a wheelchair and was accompanied by five motorcycle clubs, said she did not want children and grandchildren to go through what she went through more than six decades ago.

“I think this is something we all have to do together,” Caswell said.

The teenagers, who became known as the Clinton 12, faced an angry mob and name-calling during desegregation in the 1950s. They were pushed, had their heels stepped on, and had spit balls thrown at them. They feared that they or their families could be harmed. They faced threats and harassment, and they had to have police escorts home.

People from outside the area came to Clinton with anti-integration propaganda, a home guard was formed, and the national guard and martial law arrived, according to the Green McAdoo Cultural Center. There were white allies in Clinton, but white supremacists bombed the high school in 1958. An abandoned elementary school in Oak Ridge was refurbished and briefly used before classes resumed at Clinton High.

One member of the Clinton 12, Minnie Ann Dickie Jones, has said it was a horrible experience. She said she did not know that people could be so mean and hateful. The Ku Klux Klan would ride up and down the street with guns protruding out of their windows, Jones said.

On Thursday, Robert Willis, a south Clinton resident, recalled those days, with the Ku Klux Klan traveling through his family’s neighborhood. His father, pastor of Mount Sinai Baptist Church, invited women and children to stay at night for protection. The men would build a bonfire and stay up, Willis said.

Willis, who was a young teenager, sat on a porch with a gun.

“That broke my mom’s heart,” he said. “That’s one of the most devastating memories I have.”

It was a growing period, Willis said. Many whites didn’t have experiences with Blacks before desegregation, said Willis, who attended the Green McAdoo School in Clinton from kindergarten to eighth grade and was bused to the old Austin High School in Knoxville for ninth to 12th grades. He graduated in the spring of 1956, just before desegregation in Clinton. Willis joined the U.S. Air Force in 1958 just to get away.

His father, the pastor, told him to greet the unlovable with love.

Today, Willis said, he has many friends, white and Black.

The message of love was one of several shared by speakers at Thursday’s protest.

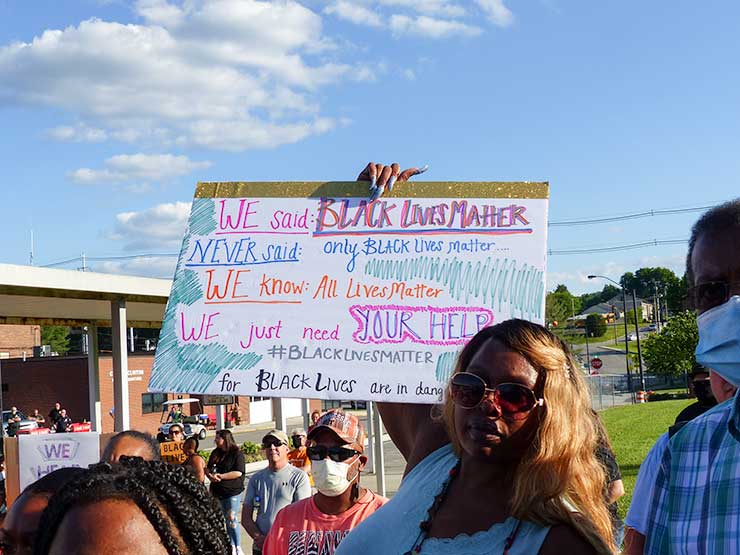

So was this message: Yes, protesters agree that all lives matter. But they want Black lives to matter too.

They said the struggle for equality stretches back centuries.

“We are still dealing with issues that should have been settled in 1865,” speaker Cleo Ellis said. That’s the year the four-year Civil War ended and the 13th Amendment was ratified, abolishing slavery after almost 250 years in the United States.

The movement will require more than a march, said Middlebrook, the civil rights leader who is a Knoxville pastor and worked with Martin Luther King Jr.

“We must not be happy to say I marched one day,” Middlebrook said.

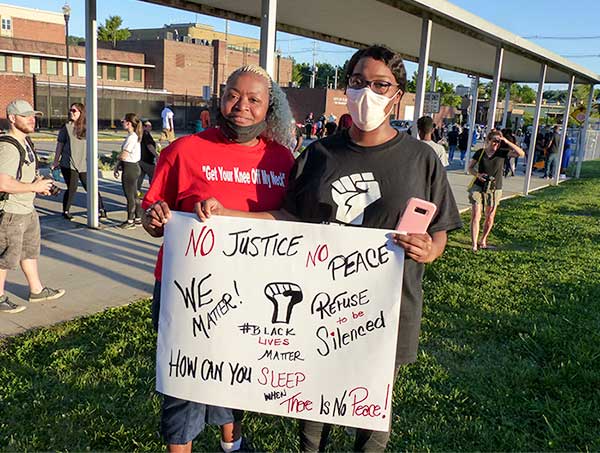

Protesters condemned structural and institutional racism, and they said they will not be silenced.

“This is an important time,” speaker James Cain said. “Too important for us to remain silent.”

“Enough is enough,” said Reverend William Caldwell Jr. “We are people just like you.”

“It’s time for change,” said Vietnam War veteran Lincoln Barton, who said he was treated differently when he returned to the United States from Vietnam.

The struggle for equality will require voting, the protesters said. Some criticized President Donald Trump.

Protesters recounted the long history of oppression of Black people in the United States dating back to 1619, including slavery, white supremacy, violations of human rights—and horrors and injustices like the brutal killing of a 14-year-old Black boy, Emmett Till, in Mississippi in 1955 after he was accused of flirting with a white woman.

The march and protest in Clinton on Thursday were among the hundreds of similar events across the United States in the almost three weeks since a 46-year-old Black man, George Floyd, died in police custody in Minneapolis as a white police officer, Derek Chauvin, kneeled on his neck and two other officers held him down for eight minutes and 46 seconds on May 25. Police had responded to a call about a counterfeit $20 bill.

Caswell, the member of the Clinton 12, commented on Chauvin’s knee on Floyd’s neck.

“That just seems horrible to me,” she said. “That’s just hatred.”

Chauvin 44, has been charged with second-degree murder, third-degree murder, and second-degree manslaughter. Three other officers at the scene, including the other two holding Floyd down, have been charged with aiding and abetting in Floyd’s death. All four have been fired from the Minneapolis Police Department.

Gary Atwater, who lives in Gadson Town in Claxton and is a pastor at New Century United Methodist Church in Harriman, said Black people have been victims for many years. They have been unjustly shot and killed by police officers and white people, Atwater said.

“We want what all Americans want: life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” Atwater said. Also justice for all, and equality in jobs and education, he said.

Protesters recognized the importance of a new generation of leaders fighting for change.

“The older people are tired,” said organizer Trevor King, who also set up a march and protest in Oak Ridge last week. “It’s time for us young people to grab the baton.”

Leave a Reply